I wrote a response to some of Arek Drozda's views on PO:

http://www.propertyobserver.com.au/...ty-and-housing-statistics-boullion-baron.html

Drozda says that principal is omitted because it equates to savings...

"Paying off the loan principal is omitted in the analysis since it equates to savings and is therefore deemed irrelevant (i.e. every dollar that is paid off becomes owner?s equity that can be drawn upon in the future)."

It's true that these "savings" may be drawn upon in the future (assuming the property retains or increases in nominal value), but they have to be borrowed back for access (with interest payable) or only retrieved in full by selling the property. I wouldn?t equate this to savings.

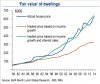

Drozda writes about a metric referred to as the "cost of buying", which measures only the cost of interest on the loan and then uses that as his basis of "housing affordability". As I've recently written on this topic, I'll quote from my last piece (

Why Serviceability ≠ Affordability):

"...Even if interest rates had remained elevated the entire period of the loan, it still ends up more affordable over the long run to have double the interest rate, but lower price to income ratio. Not only that but it would be faster to save the deposit given that it's a lower amount (relative to income) and I haven't taken into account the higher interest rate on saving for the deposit which would have benefited the 1992 scenario. Costs such as stamp duty which are tied to the price paid would be lower too. Finally, higher interest rates tend to come with a higher rate of inflation, so the real value of the debt would be reduced faster as wages increased, meaning the buyer in 1992 would have found it easier to ramp up the level of repayment.

...When considering affordability we need to take a holistic approach and not use a simple snapshot of a single repayment as the basis to make judgement calls on whether house prices or a mortgage used to purchase them is affordable. A mortgage is a long term commitment and shouldn't be treated so trivially by market commentators."

Drozda's argument in this article does show how buyers have been able to comfortably service mortgages at these higher prices (as he puts it "rediscovered their true financial capacity"), mostly a result of lower interest rates, but as I've shown that doesn't make them affordable unless you're of the opinion that serviceability is the same as affordability. I think it's deceptive to speak to the affordability of 'buying' a home, but only taking into consideration the cost of servicing the interest portion of a mortgage.